The Perseverance of an Independent Tibetan School: The 30-Year Journey of Jigme Gyaltsen Ethnic Vocational School

一所独立藏语民族学校的坚守——吉美坚赞民族职业学校的30年

In July 2024, Jigme Gyaltsen Ethnic Vocational High School, which had operated independently for 30 years, announced its closure. Known as the best Tibetan-language educational institution and a private welfare school in the greater Tibetan region, it has now come to an end. The author of this article once served as an IT technician at the school, handling numerous digital archives and witnessing the establishment, struggles, development, and eventual forced closure of this institution on this land. Now living overseas, the author learned of the school's shutdown. However, due to censorship, former colleagues and Tibetan friends could not convey their sorrow. The author took up the pen to write this detailed recollection.

The original manuscript was published in Chinese on Mangmang: 一所独立藏语民族学校的坚守与落幕——吉美坚赞民族职业学校的30年

On July 14, 2024, in Golog Prefecture, Qinghai Province, the esteemed monk of Ragya Monastery and renowned educator Jigme Gyaltsen announced via a bilingual Tibetan-Chinese post on WeChat that the independently operated Jigme Gyaltsen Ethnic Vocational High School, which he founded, would be closing down after 30 years. The school had long offered free admission to students from farming and herding communities across the Tibetan regions of five provinces. It was regarded as one of the finest Tibetan-language educational institutions in the Greater Tibetan Area. This legendary private welfare school on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau has thus come to an end. The announcement emphasized that the closure was not due to the will of any individual or organization. Still, it was based on the national standards for vocational schools and relevant directives from the Qinghai Provincial Committee.

Some have commented that "black snow" has fallen over the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, extinguishing a beacon for the Tibetan people.

Ragya Town, a small settlement along the Yellow River in Golog Prefecture, Qinghai Province, is home to this iconic institution. Here, when locals say “the school,” everyone knows it refers to this one—it feels like there is only one school in Ragya. Between Ragya Town and the school lies the mountain "Ani Qungong," meaning "Great Roc Spreading Its Wings," at the foot of the mountain stands Ragya Monastery, the first monastery on the Yellow River. I will use "Ragya School" in the following text to refer to Jigme Gyaltsen Ethic Vocational High School.

From 2018 to 2019, I briefly worked as a network technician at this school. While there, I became deeply immersed in its environment and worked closely with many digital archives. I witnessed Ragya School's founding, struggles, development, and eventual forced closure on this land through this. I witnessed its rise and fall, its joys and sorrows.

This school was called the "Harvard of the Tibetan people," its forced closure carries profound significance for the entire Tibetan region. Now, living overseas, I learned of the school's shutdown. I saw my Tibetan friends on social media drowning in tears, yet unable to express their grief in their native language due to censorship on social media like WeChat.

I deeply feel a connection between myself and this distant school, and the sorrowful cries from afar resonate with me. Since I am overseas, I decided to write it all down.

01 A Fusion of Tradition and Modernity: An Educational Experiment

Jigme Gyaltsen (hereafter referred to as “the Principal”) was a monk from Golog who founded Ragya School in 1994. It was the first private welfare school in Qinghai Province and a pioneering educational reform in Tibetan regions at the time.

Traditional Tibetan society primarily relied on monastic education. For both men and women, becoming a monk or nun and going to a monastery was often the only way to receive an education. Monasteries had a comprehensive education system comparable to modern primary and secondary schools, with various degrees and certifications. For example, the Geshe degree is akin to a doctorate in Tibetan Buddhism. Families would willingly support their children’s monastic studies by providing food, clothing, and pocket money. In Tibet, monasteries functioned as more than just schools; they also served as welfare organizations, banks, hospitals, and academic institutions.

The Principal, who had received higher education, graduated from the Advanced Buddhist Institute founded by the Panchen Lama in Beijing before deciding to return to his hometown. At that time, Amdo Tibet was underdeveloped and lacked educational resources. Traditional monks were unfamiliar with modern knowledge and skills such as law, Mandarin, or computer science and had no place to learn them. Meanwhile, Tibetan children from nomadic families, due to their traditional pastoral lifestyle, had limited access to education. For example, in 2020, a Tibetan herdsman named Tenzing Tsondu(DingZhen) became an internet sensation in China because of his handsome appearance. After achieving fame as a livestreamer with millions of fans, he was revealed to be illiterate in Chinese. This wasn’t unusual in traditional Tibetan society, as herding on the grasslands didn’t require literacy.

To promote modern education in Tibet, the Principal combined the traditional monastic education system with the modern school system to create a unique integrated model that admitted both monks and lay students of all ages. Since pastoral families in Tibetan areas don’t face the same academic or employment pressures as in mainland China, it was common to see young teenagers studying alongside older herdsmen with beards who had spent the past decade tending sheep in the same classroom. Ragya School placed no restrictions on age, religious status, or sect. Even students who were completely illiterate at the time of admission were treated equally. They lined up to register and were placed in classes according to their level of Tibetan literacy.

As a welfare school, Ragya School adhered to the principle of “education for all without discrimination.” Each year, the school enrolls about 200 students; sometimes, even the principal's relatives have to wait in line for three years before being admitted. Priority was given to orphans, dropouts, overage youth, and young monks from poor rural and nomadic families. The school even accepted Mongolian, Han, and other ethnic students and tulkus from various regions.

Once admitted, students were provided with free tuition, meals, and accommodation. The school’s curriculum was rooted in the traditional Tibetan “Ten Sciences” while incorporating modern scientific knowledge. The school includes a junior high school and a senior high school. The junior high school offered foundational courses such as basic Tibetan, Mandarin, and mathematics, while the senior high school evolved into a vocational high school with seven specialized programs tailored to Tibetan culture: Tibetan medicine, advanced Tibetan studies, computer applications, tourism, English, arts and crafts (Thangka painting), film production, and alpine guiding. Most of these programs were developed as school-based curricula with published textbooks.

The school accommodated more than 1,000 students, ranging in age from 6 to 42, with about one-third being monks. Students came from farming and herding regions across Qinghai, Tibet, Sichuan, Gansu, Inner Mongolia, and beyond.

02 Difficult Start-up, Unique Operational Methods

The establishment of the school was initially very difficult, lacking resources in many ways: funding, policies, teachers, and construction were all challenges. The principal was neither a Rinpoche nor a distinguished eminent monk. When the school was founded, he only had 3,000 yuan in deposit. He had to travel extensively, seeking loans and resources, hoping to persuade people to support his endeavor. Eventually, he gained the support of Rinpoche from various monasteries and the then-governor of Golog Prefecture. After many twists and turns, he secured land and obtained the government's approval to open the school.

When the school was first established, the campus was built with the help of the nine students who initially enrolled. At that time, the students and teachers had no accommodation and had to live at the Ragya Monastery. During winter weekends, they would go to nearby mountains to gather branches and yak dung to keep the stoves burning for warmth. Local villagers, monks from Ragya monastery, and the school’s students worked together, using bags to carry soil and level the ground to create the sports field. They also felled trees to construct the first school buildings.

In a documentary about the school’s history, I saw how the wood for the early buildings was sourced. The students were allocated into three groups: the first group felled trees upstream of the Yellow River; the second group floated the logs down the river to Ragya; and the third group retrieved the wood from the shallow banks of the Yellow River near the school. This was how many of the school’s early buildings were constructed.

Principal Jigme Gyaltsen was an educator and an entrepreneur. The school initially maintained its independence through funding provided by the "Snowland Treasures" dairy company (hereafter referred to as the Dairy Factory), which he established. The factory’s early techniques were learned from two Europeans, and its dairy products were initially exported overseas. The dairy business provided income for herders and all its profits were used to cover the school’s expenses, allowing it to offer free education and boarding for students and pay staff salaries.

By the time I had just graduated from university and began to engage with the operations of social organizations, I was amazed at how the principal, who had spent years on the plateau, learned and established such a progressive concept of “social enterprise.” By using this advanced model, he promoted sustainable development in pastoral regions.

Later, however, the export channels for the dairy factory’s products faced issues, and the products could no longer be sold overseas, leaving the domestic market as the only option. Over time, the factory’s efficiency declined, and the principal had to seek funding from other sources. Given the influence of Ragya School and the principal’s reputation, fundraising was not initially difficult. At that time, various social sectors and local governments were eager to provide resources to the school: The Hong Kong Jockey Club funded the construction of modern school buildings. The Trace Foundation supported several school expenses. Beijing Blue Charity Foundation donated many books to the school library. Government subsidies were provided to impoverished students for living expenses.

However, transferring donations to the school’s accounts became more difficult due to increasingly restrictive government regulations and policies. Overseas funds were no longer accepted, and even domestic funds could not be accessed. Gradually, the school began to experience financial difficulties. Before it closed, it was said that the school had gone three years without paying regular salaries.

The teachers’ salaries had never been high to begin with, and when the financial issues arose, the school stopped paying the salaries of monastic teachers. Since the monks don’t have families to support, the school provided their meals and accommodations, and their families could provide tiny allowances for personal expenses. However, lay teachers, who had families to support, found it much harder to cope. Many had no choice but to leave the school.

One teacher, who had studied at a university on the mainland, told me that working at Ragya school was a social service but not a service without an end. After serving for some time, one had to leave—continuing serving was not sustainable.

In October 2018, the Trace Foundation issued an open letter announcing its gradual cessation of most activities in Tibetan areas of China, citing fundamental changes in conditions on the Tibetan Plateau for an overseas foundation. The Trace Foundation, headquartered in New York, funds and supports community and educational initiatives in Tibet. Many private Tibetan-language schools, including Ragya School, have received their support.

At the time, I was in China and completely unaware of this significant change. I had only heard sporadically that introducing China’s Foreign NGO Law had made it difficult for foreign donors to fund initiatives like ours. Back in the day, my knowledge of Tibet was very limited, and I didn’t know where to find reliable research materials to learn. Our projects run by our organization in Tibetan areas also faced challenges: we struggled to find full-time teachers willing to work on the Tibetan Plateau and secure funding partners interested in supporting this project.

As a recent college graduate on a short-term network technician assignment, I was just beginning my journey on this plateau. My responsibilities were to consolidate and transform the outcomes of earlier projects and wind down some of the initiatives.

03: Holistic Education in Single-gender School

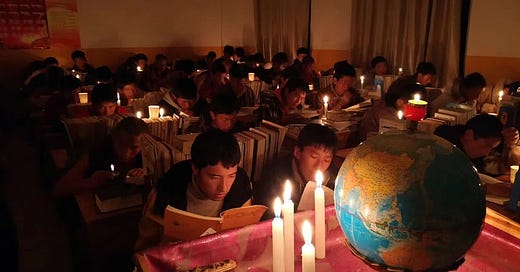

Ragya School is an all-boys school. Situated in a pastoral area at an altitude of nearly 4,000 meters on the grasslands along the upper reaches of the Yellow River, the campus is surrounded by freely roaming rabbits, marmots, and herds of grazing yaks and sheep. Scattered groups of students often sit in clusters, reciting the key points of their daily lessons. Every morning and evening, the sound of their reading reverberates throughout the campus, forming a unique and vibrant sight on campus.

Additionally, the students, whether laypeople or monks, engage in daily debates, either one-on-one or in groups. Holding prayer beads in their hands, they often debate so passionately that their faces turn red, and words fly back and forth with fervor. Even though I couldn’t understand what they were arguing about, I could feel the youthful energy and determination around them.

The principal named the school " Gang Jong Sherig Norbu Lobling institution" (meaning "Snowland Institute of Wisdom" གངས་ལྗོངས་ཤེས་རིག་ ནོར་བུའི་སློབ་གླིང་། 雪域知明院 ). Beyond the daily outdoor group recitations and debates, the school offers various vibrant extracurricular activities held at set times each week. These include Tibetan-Chinese-English trilingual debates, speech competitions, brainteasers, poetry recitals, tongue twisters, comedic skits, historical quizzes, science and legal knowledge competitions, essay-writing contests, and Tibetan neologism translation competitions. Almost all these activities are student-organized, with senior students passing down their experience to the younger ones.

The school places a strong emphasis on multilingual education. I still remember that during sports festivals and school anniversary celebrations, the announcements on stage were made in as many as five languages: Amdo Tibetan, Lhasa Tibetan, Kham Tibetan, Mandarin, and English. The linguistic differences between Tibetan dialects can be significant; for example, an Amdo speaker meeting someone from Lhasa might not be able to communicate at all and might have to resort to Mandarin. In the past, literate monks could communicate through written Tibetan, as its script was standardized. At Ragya School, students can master this writing system and the written language commonly used among Tibetan intellectuals without needing to ordain as monks.

In traditional Tibetan areas, women had very limited access to education. To change this, the principal began applying to the local education authorities in 1997 to establish a girls’ school. The principal said, “Girls’ education is mothers’ education, and mothers’ education is education of humanity.” After raising funds through various channels, he founded the Grassland Girls’ School in 2005 at the foot of the sacred Ragya Mountain. This was the first girls' school in Tibet, and its students were the children of nomadic families from across the area. The principal believed that developing a girls’ school would allow girls to organize their own activities independently, ensuring their participation wasn’t overshadowed by boys.

I had few opportunities to interact with the girls' school students; most encounters were public. They were generally much shyer than the boys. I once shared a meal with them and had a simple conversation. I was always an outsider to the circle of local teachers, and the students regarded me as a mysterious figure, treating me with extra respect, which only deepened the divide between us. When we met, it was usually during school events where they performed programs at the vocational high school campus where I worked.

The girls always wore elaborate Tibetan chupas suits. Their faces glowed with a faint blush, nervousness, and a gentle smile. Their hair was meticulously groomed, shining, and neat. Unlike the boys, who would play, wrestle, and run around, the girls were quiet and shy and often avoided direct eye contact. Unfortunately, I didn’t have many chances to explore their world further.

Like the boys' school, the girls' school also offered a variety of activities, including daily one-on-one debates based on the school curriculum. The principal believed that “Logical debates not only enhance reasoning and communication skills but also help develop intelligence, strengthen memory, and deepen critical thinking in youth.” Through gradual exploration, he skillfully integrated traditional monastic logic debates (pramana) into modern education, using traditional debating methods to explore modern knowledge.

Teachers adapt the school’s curriculum to fit Tibet's unique context. For example, their English textbook was called “Highland English Reader,” written in English to describe the plateau's natural landscapes and culture. An English teacher explained, “Mainland textbooks are not suitable for us. Teaching students to express our culture in English is the goal of our education.”

Many of the school’s teachers are elite intellectuals with multilingual proficiency and diverse academic backgrounds. In philosophy classes, they teach everything from the Tibetan philosopher Pandita masters to Hegel and Nietzsche. In astronomy classes, they discuss stargazing and calculate the Tibetan New Year (Losar) and Shoton Festival using the Tibetan calendar. In English classes, a teacher born in India recites English poetry fluently and teaches students how to converse in everyday English. In computer classes, students learn to install Tibetan input methods and convert corrupted files displaying garbled characters into Tibetan text. They practice making slideshows and designing magazine layouts as though they are constantly preparing to apply their skills in real-world scenarios.

In my view, the school embodies the principles of holistic education, aiming to cultivate students as well-rounded intellectuals proficient in their native language and culture. Each senior graduate completes one or two final projects, including township chronicles, family genealogies, monastic histories, and creative works like paintings, poetry collections, academic papers, music videos(MV), documentaries, or short films. These projects have led to a vibrant collection of independent publications and films.

I sometimes felt the students’ cultural life was as vibrant as university life. The key difference was that creating these projects wasn’t about meeting graduation requirements but stemmed from a pure desire for cultural exploration and intellectual curiosity.

04: Public Punishment

If there’s one teaching method at the school that I found hard to accept, it would be the strict disciplinary system. My former teacher once told me that I should attend the school’s weekly assembly if I had the chance, but I need to be mentally prepared—because I might find it shocking as someone from a different cultural background. During these assemblies, teachers publicly reprimand students who had misbehaved in the past week, sometimes even slapping them in front of everyone. The most severe infractions I can recall were related to integrity, such as cheating on exams or secretly keeping a mobile phone.

On a sunny afternoon, I was invited to observe one of these assemblies. The gathering reminded me of the school meetings I had in my own middle and high school, conducted entirely in Tibetan. The theme of the meeting was “Learning from Lei Feng Day.” After the main topic was addressed, there was no singing of the national anthem. Instead, the atmosphere grew tense, as if everyone knew what was about to happen.

I retreated indoors, too nervous to take out my phone to document the moment, waiting silently for it to unfold. Three students walked onto the stage. My view from the teaching building was behind them. I couldn’t see their expressions clearly. They bent forward, heads bowed, facing an audience of hundreds of students. A teacher, referred to as an Aku (a local honorific), began announcing the reasons for punishing the three students. Then, he slapped each of them a few times. The slaps didn’t seem heavy, but I felt shocked.

As someone raised in Han Chinese society, I had never experienced such a severe disciplinary approach. (They always occur in an informal way). A voice in my head cried out: This shouldn’t be happening! This is corporal punishment. How can they do this? Another voice countered: Perhaps this is a remnant of monastic education in the region. Should I respect their ethnic customs and rules? I felt torn, shocked, and confused. The moment made such an impression that I can no longer recall how many slaps were given or how I left the assembly and returned to my dormitory.

Later, I asked a few Han Chinese teachers who had also taught at the school, and none of them had ever attended these assemblies. I felt like a fool who had clumsily stumbled into the Middle Ages, utterly unprepared for the severity of the punishment I witnessed.

Traditional Tibetan Buddhist monasteries have a monastic position known as gegue格贵, responsible for managing the monastery’s roster and enforcing discipline. Han Chinese often refer to them as “iron-rod lamas.” I couldn’t confirm whether this style of public punishment was connected to the gegue, but the teachers at the school saw it as a positive way to instill a clear sense of right and wrong in the students. Monks in monasteries, they explained, also faced similar punishments for breaking rules or failing to memorize scriptures.

The school’s educational reforms were part of an effort to secularize and modernize traditional monastic education. However, it was obvious that this method of punishment was one aspect they had yet to reconsider or reform.

05: A Legendary Existence

I once asked a Han Chinese teacher who had been teaching at the school for many years how this school differed from the inland schools where she had worked previously. She replied that the students had an intense thirst for knowledge and a much closer teacher-student relationship. She used the phrase “respecting teachers and valuing the Rules” (尊师重道), a term that felt distant to me, something I had read in books about the past but had not met in the real world.

Every graduation season, students would pitch tents on the grasslands, host film exhibitions, have picnics, play games, and celebrate. After graduation, some students pursued higher education, others returned to monasteries for further spiritual practice, returned to their hometowns, or stayed at the school as teaching assistants or teachers. A strong alumni network had formed among the students. Many of the teachers at the school were former students who, inspired by its educational philosophy, returned to teach despite receiving modest salaries and enduring the harsh conditions of the plateau. Some graduates even went back to their hometowns to fund schools in their hometown, spreading the seeds of Tibetan education across the Tibetan Plateau.

It wasn’t until the school was shut down that I realized it was the last private school in Tibet to teach in the Tibetan language. Looking back at its history, I often feel that this school’s journey from humble beginnings to 30 years of operation in Tibet is nothing short of legendary—a mythical existence.

In recent years, the government has increased investment in public schools in Tibetan areas, even teaching high school students to use robots and artificial intelligence. After seeing a Tibetan high school student on the news say, “In the future, drones can be used for herding,” it reminded me that using the modern photography equipment such as action cameras, gimbals, and drones that the students at Ragya school had already been using for years. These tools were among their favorites. However, I believe the difference lies in this. At this school, pastoral children were taught how to use drones and similar technological tools to improve productivity in their communities and enrich their cultural lives. Public education, however, seems to select a subset of students to teach them high-tech skills while instilling the idea that they are superior and should stay in cities to focus on technology—no longer herding livestock in the future. At Ragya school, technology was a tool for the collective welfare, not a sieve to divide people into hierarchies.

Public education, whether through boarding schools in Tibet or inland high schools, seems to uproot young Tibetans, transplanting them from their lands into urban environments. A small number of academically successful students may become government officials or teachers. However, most who fail to gain admission to universities and secure formal jobs can no longer return to their nomadic way of life on the grasslands. They often end up working as restaurant staff, drivers, tour guides, chefs, or hotel workers in county towns.

Over the past 30 years, Ragya School has nurtured many students who are not only well-educated in modern subjects but also proficient in Tibetan, with deep cultural roots. These students have made meaningful contributions in their fields across the Tibet Plateau, becoming intellectuals, educators, artists, writers, civil servants, and entrepreneurs.

Other students went on to work for NGOs, implementing environmental protection and snow mountain monitoring projects in Tibet. Afterward, he opened a guesthouse in Xining to foster cultural exchange between Tibetans and Han Chinese. One student made a documentary about the seasonal changes of the Yellow River and dreamed of building a natural history museum in their hometown. Another opened a typing and printing shop in their county, turning it into a cultural company. Some went to big cities to become professional photographers or video editors, venturing into the film industry. One student, the eldest son in his family, excelled academically and aspired to move to the city but ultimately decided to return hometown to take over the family’s herd of hundreds of yak and sheep.

One monk student returned to his monastery after graduation, writing a book about his monastery's history and tracing his family's migratory history. He told me regretfully that publishing a book now is extremely difficult due to the high cost of publication permits and stringent censorship. Independent publications are not allowed to be mailed. A bookstore in Ragya town that sold a few unpublished books was shut down, and the owner was arrested. I had visited that bookstore before; it was one of my favorite places in the town.

To be continued….

Due to space limitations, this is the first half of the article. I will publish the second half of the article shortly: School’s Crisis and Closures. I completed the English translation myself with the assistance of ChatGPT. I am not a professional scholar of Tibetan culture, so if you are not satisfied with my translation, please do not hesitate to contact me to help me improve it. Gachi che (Thank you!) :P

Here is the second part: